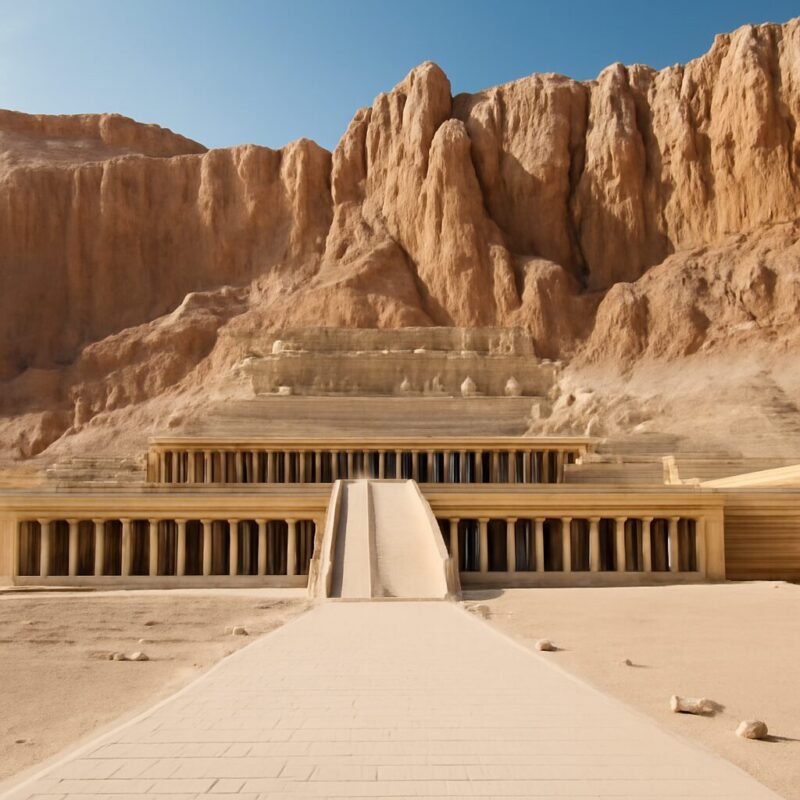

Carved into the sheer limestone cliffs of Deir el-Bahari, the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut feels less like a tomb and more like a bold, architectural declaration. It rises in three sweeping, colonnaded terraces, a stark, geometric marvel against the amber rock face, daringly modern even after thirty-five centuries. This was the great monument of the female pharaoh who ruled Egypt as a king, and every clean line whispers her ambition. While her actual burial chamber lies hidden deep within the mountain behind it, the temple itself was her public testament. Rampways lead past reliefs depicting her divine birth and the legendary trading expedition to the land of Punt, stories etched in stone to legitimize her unprecedented reign. The air here is dry and still, scented with dust and history, in a colonnaded courtyard that once held fragrant frankincense trees. It is a place of profound quiet power, where one woman’s audacious vision permanently altered the horizon.

Who Built Tomb of Hatshepsut?

Who Built the Tomb of Hatshepsut?

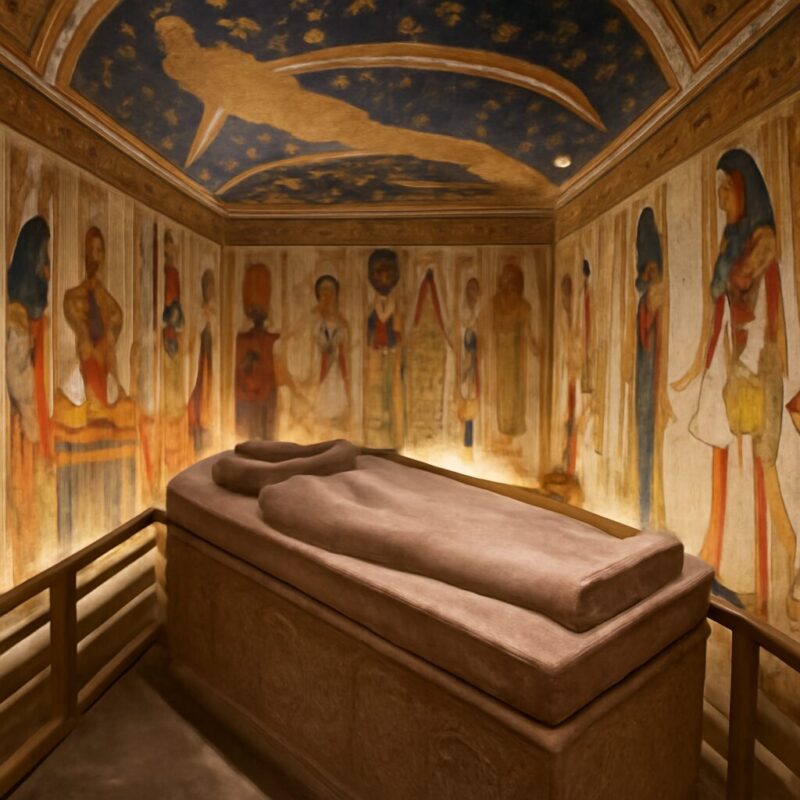

The Tomb of Hatshepsut (designated KV20) in the Valley of the Kings was built for Hatshepsut, one of ancient Egypt's few female pharaohs who ruled during the 18th Dynasty (c. 1479–1458 BCE). The tomb's construction was commissioned by Hatshepsut herself, likely overseen by her chief steward and architect, Senenmut, who was responsible for many of her building projects.

Why Was It Built?

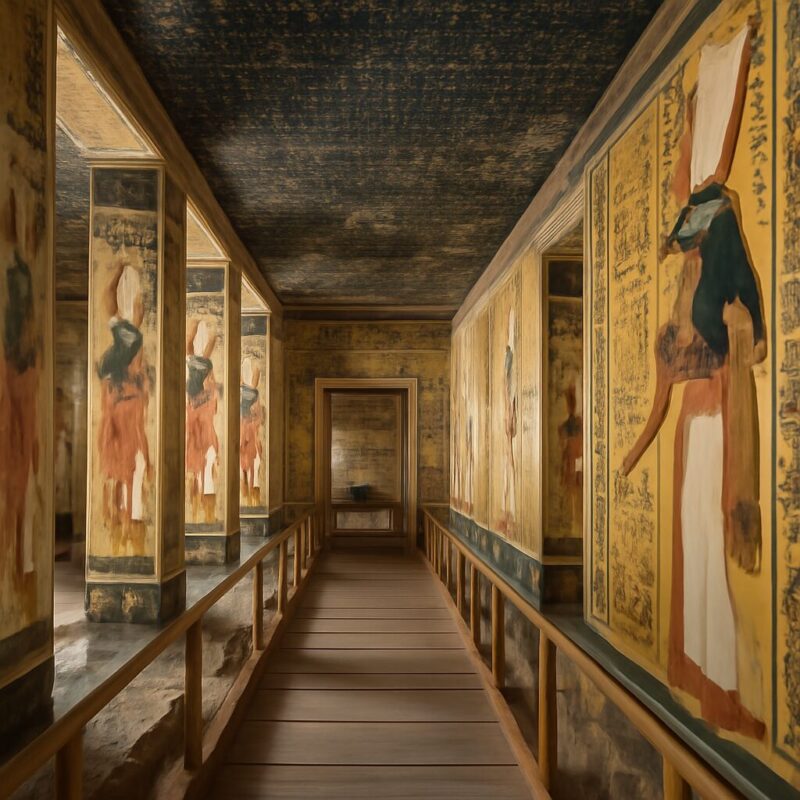

The tomb was built to serve as the eternal resting place for Pharaoh Hatshepsut and her father, Thutmose I, whose mummy she relocated there. Its construction was a critical part of the royal funerary tradition, designed to protect the pharaoh's body and possessions for the afterlife and to facilitate her journey to the realm of the gods. The tomb's deep, winding structure reflected both the secrecy desired for royal burials to deter thieves and the symbolic descent into the underworld.

Cultural Context of New Kingdom Royal Tombs

Hatshepsut's reign was part of the New Kingdom period, a golden age of Egyptian architecture and imperial power. Royal tombs from this era abandoned the highly visible pyramid form of the Old Kingdom for hidden, rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings. This shift was driven by a desire for greater security against tomb robbers and a theological emphasis on the tomb as a hidden gateway to the afterlife, intimately connected to the solar cycle and the god Amun.

Other Relevant Tombs from the Provided List

As a pharaoh of the New Kingdom, Hatshepsut's tomb is part of the same royal necropolis as many other famous Egyptian rulers. Highly relevant tombs from your list built in the same cultural tradition include:

- Tomb of Thutmose III (her successor).

- Tomb of Seti I (19th Dynasty).

- Tomb of Ramses II (19th Dynasty).

- Tomb of Tutankhamun (18th Dynasty).

For broader context of monumental Egyptian tomb architecture from earlier periods, you can explore the Great Pyramid of Khufu or the Step Pyramid of Djoser.